I found out the day after my 21st birthday that my Aunt Sharon, who was also my godmother, was diagnosed with cancer. She was diagnosed on the day of my actual birthday, but my mom didn’t want to ruin my birthday by telling me that. I was upset, of course, but I repressed it, because I was also optimistic. People recovered from cancer all of the time, and besides, this was Sharon we were talking about. Sharon had always been the kindest, most loving, generous person I had ever met. Hers was a positive presence that, looking back, perhaps I had taken for granted. Regardless, I was hopeful.

Not even two weeks later, I received another call from my mom, telling me that Sharon’s cancer was Stage 4. I wasn’t sure what to do. I cried to get it out of my system, but I think I still didn’t know what it even meant. It didn’t feel real. I was only accepting the information I needed to, and blocking everything else out. Even now, I still don’t know exactly what kind it was. I didn’t want to ask questions. I think the fact that I didn’t ask questions only contributed to how unreal the whole experience felt.

Regardless, I continued to push it to the back of my mind. Part of me was holding on to hope that some kind of miracle was going to happen and she was going to suddenly recover.

But, unfortunately, she didn’t. A couple weeks later, I found out she only had a few days. Two days later, she was gone. Again, I was devastated, but there was also this strange sense of numbness that came with receiving all of my information through text messages and phone calls. My mother was right beside her, holding her hand and giving her medicine and watching her take her last breaths. Meanwhile, I might as well have been hearing about a stranger on the news.

It started to feel a little more real a couple of days later, when my whole family drove to Antigonish for the wake and the funeral. Surrounded by people who were all grieving for the same person, and seeing my uncle and cousins – that added some clarity. The whole point of wakes and funerals are to give you closure, right? It was supposed to do that, and it did a little, but to this day, I still don’t feel like it’s real. It’s as if I feel sadder seeing what this loss has done to my family than I actually do for my own loss.

It wasn’t what I thought loss was going to feel like. Then again, I’m not really sure what I thought it was going to feel like. Nothing really prepares you for it, and nobody really experiences it the same way.

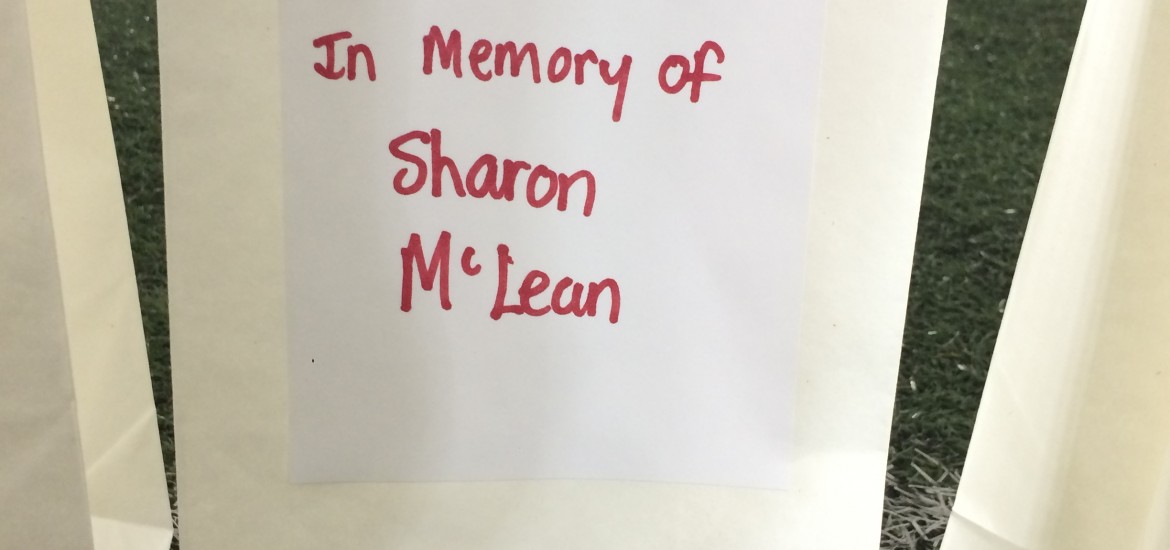

Recently, I participated in my second Relay For Life, the first one that meant something. During the moment of silence, I stood in front of the luminary I had dedicated to her and silently sent her a few words. All of my friends on my team stood by my side, each of them reflecting on someone they had lost. It was this powerful, connecting moment, and it made me realize something.

Nobody experiences loss or pain the same way, but unfortunately, everyone does experience it. There were so many people who I thought I knew so well, only to find out that they had experienced unimaginable hardships. I think it’s easy to isolate ourselves when we’re going through painful times and to believe that no one understands how we feel.

It’s not like that. People do understand.

I don’t have the same painful, final memories of Sharon that some people do. I didn’t get to give her a final goodbye, but maybe that’s for the best. Instead, I remember her beaming smile. I remember the way she would always spend way too much on my birthdays or at Christmas. I remember the way she and my mom would always drink glasses upon glasses of red wine after not seeing each other for a long time.

Mostly, thanks to a perfume-sprayed scarf that her daughter gave me, I’ll always remember the way she smelled.

These things aren’t much, but they’re enough.